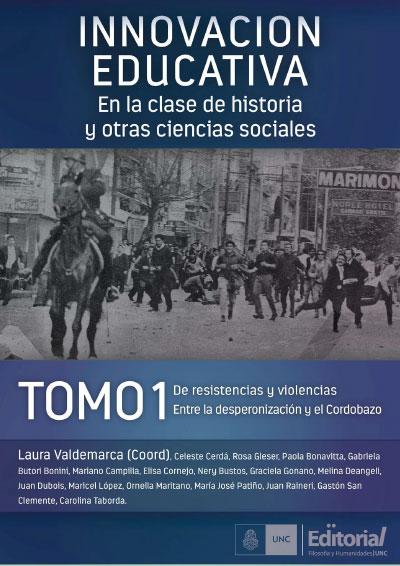

Educational innovation in history and other social sciences classes: reflections and materials for teachers. Volume 1. Resistance and violence: between de-Peronization and the Cordobazo

Keywords:

history teaching - pedagogical innovations, social sciences - study and teaching, recent history - teaching, Córdoba (Argentina), oral history - use in teaching, historical memory - teaching, secondary education - teaching innovations, oral testimonies - educational use, political violence - teaching, Peronism - teaching, de-Peronization - teaching, Cordobazo, 1969 - teaching, audiovisual resources - use in history teaching, citizenship - training - history teachingSynopsis

Those of us who created this book as the Microfilm Research and Production Team participated as researchers in the project Memory and Recent History: Search, Preservation, Uses, and Research Based on Oral Testimonies, based at the María Saleme de Burnichon Research Center at the National University of Córdoba.

The project to produce audiovisual materials on local and recent history began several years ago and addressed two concerns that have been on our minds for many years. On the one hand, we worked with oral sources to reconstruct processes of recent and local history, generally very close in time and involving issues that affected so-called minorities: families and/or women living in poverty, political persecutees forced into exile or internal exile, illegal occupants of land on which they built their homes and organized their daily lives, etc. During the interviews, our witnesses often recounted anecdotes or episodes that we felt were suitable for capturing the attention of a teenager in a history class.

This led to the second question: how to make the analysis of historical processes meaningful for adolescents and in secondary school and contribute to the re-legitimization of the educational system as a space for knowledge construction, while at the same time spreading to other audiences the fascination that we feel for investigating the past. The initial intention of the project was to recover everyday life in order to teach history in secondary school. Then other questions arose. One of them concerns the potential of oral testimony to help understand the climate of an era, because those who transmit their experiences do so from a very personal perspective, helping us to understand what the protagonist felt during the episode being narrated. It was a first opportunity to rethink and respond to the teaching of history from a more friendly perspective than that of the school textbook, which generally presents an immobile structure that is alien and distant from the reality of a student in Cordoba.

These initial questions and insights were extremely useful in helping us overcome our deep concern about the teaching of history, which was rooted in a greater and more profound distress felt by many history teachers and historians and stemmed from the crisis in secondary and sometimes even university education. The questions we asked ourselves among colleagues could be summarized as: why teach history in a world that repeats its failures in various forms of material and symbolic violence, from persecution to exploitation, discrimination, poverty, and exclusion? Perhaps what needs to be changed is the question itself, and it is no longer just the content of history, but the method and how to teach history in order to rethink a better society. After all, perhaps history class is one of the few opportunities that children and adolescents have to learn about our past and understand it from a place of action, criticism, openness, and concern for citizenship; a past that is not closed in the way it is generally explained by the historiography adopted in schools and that perhaps does not go anywhere in particular, as intended by a teleology of history, now outdated in university classrooms but still present in common sense, even among many history teachers and most citizens.

It is possible to continue teaching on “autopilot,” pretending that everything is fine, and this is the alternative chosen by many teachers at all levels. However, it is more complicated to continue teaching in a crisis situation because crises challenge us, irritate us, and often force us to find answers. From our work and experience as teachers and researchers at Argentine public universities, we also try to provide some answers to this question. The first step was to imagine new materials whose format would be more relevant to the subject we are teaching, the one with whom we must generate the empathy necessary for learning: the 21st-century teenager. This is the young person who is caught between childhood and adulthood, whose era is that of video games and channel surfing, and who is also the future citizen of a globalized world, where time and space—two fundamental components of history—take on unusual dimensions due to the use of technology.

Chapters

-

About the authors

-

Contributions from the University to the teaching of local and recent history

-

From recent and oral history as a subject of research to the production of audiovisual micro-programs for teaching social sciences and humanities

-

The recent past at school. Notes on the challenges of teaching history in times of dis/memories.

-

Violence, beatings, and difficulties in civil coexistence

-

Perón, Paredón, and after. De-Peronization as a strategy for forgetting

-

Rebels with a cause. Young people, protest, and mobilization

-

The Cordobazo, a time for the brave

Downloads

Published

Categories

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.